US Trucking Primer II : Truckload Carriers Overview

Continuing the analysis of the trucking industry and cycle from two weeks ago, this article provides an overview of the truckload carrier segment.

Truckload carriers are the most ‘pure-play’ of the industry’s segments, because of their exposure to for-hire rates, because they own large fleets of trucks and drivers (operational leverage), and because their lack of other meaningful competitive assets.

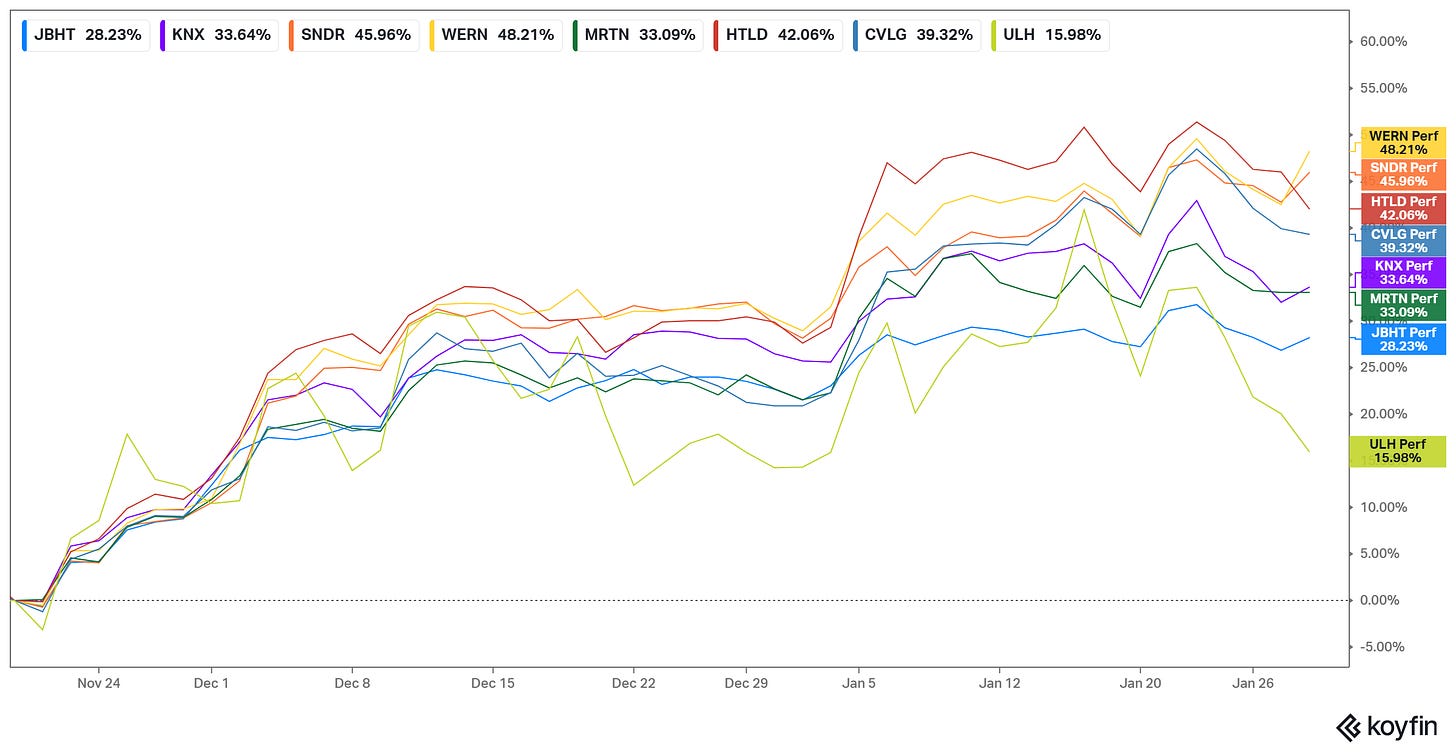

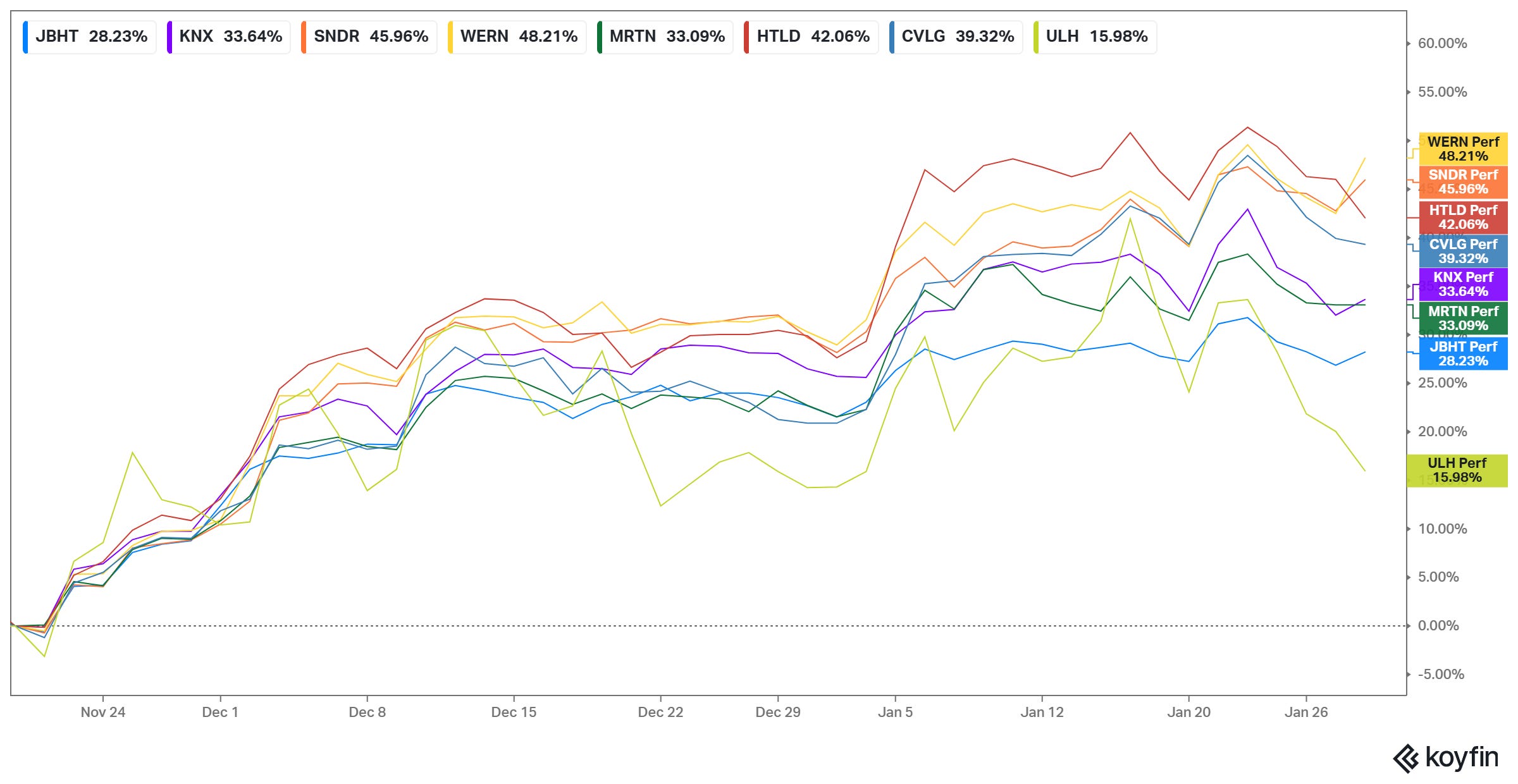

This makes them a leveraged play to the trucking cycle, and their stock prices have performed rather spectacularly in the past three months, in anticipation of a much awaited cycle turnaround.

The article provides an introduction to each of the companies, and applies a model for long-term cyclical valuation based on their returns on tangible capital employed, leverage capacity, and growth potential.

A long-term anchor based on what these companies can truly earn at peak, average, and bottom of the cycle, is important for more fundamental focused readers expecting to find companies for the long-term. It is also relevant, however, for speculative focused readers expecting to play the cycle, because it gives us an idea of whether expectations are depressed, fair, buoyant, or euphoric.

All of the overviews are open, except for the company that called my attention the most, which is behind the paywall at the end of the article.

On the road we go!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in the Blog are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual or on any specific security or investment product.

Truckload Carriers mini-review

Truckload carriers move full truckloads from point to point. They do so by operating (and owning) trucks and trailers via hired drivers, plus some adjacent assets like maintenance shops, truck stations (basically an empty plot of land where tractors and trailers can be dropped, plus a small admin and resting space), and not much more.

The complexity of a truckload network is not very high, and in some cases can be reduced to only owning (or even leasing) the trucks and hiring the drivers, with all adjacent services provided by third parties. It is low-entry and fairly commoditized.

Within truckload, we can differentiate three specific modes.

The simplest is one-way truckload for-hire, which is arguably the most commoditized and more exposed to spot rates. Most of the companies covered have tried to reduce their exposure to this segment, except for some cases (HTLD, KNX in part). The more a company is exposed to one-way, the more leveraged it is to the trucking cycle.

Another important mode, particularly for public companies, is dedicated, where the company manages fleets that operate for specific clients, usually doing scheduled routes. Dedicated is affected by the same commoditization and depends on the spot market, but contracts can be longer, and therefore, cycle volatility is a little lower. The stability can provide for better planning and asset utilization as well.

Finally, we have intermodal, which is a mix of shorter truck hauls (called drayage) and longer, usually intercontinental, railroad hauls. I don’t find intermodal has a lot more barriers to entry, because the key network assets are owned by the railroads, not the trucking carriers.

The EBIT/TCE method for valuing the carriers

The goal of this section and of the primer in general is to provide an estimate for the value of these carriers from a long-term perspective. For this, I use the pre-tax returns the companies have earned on their tangible capital employed in the past to estimate their earnings capacity today across a whole cycle (bull and bear).

Tangible capital employed is Total Assets - Goodwill and Intangibles - Working capital liabilities (excluding current debt and current leases). The numerator is EBIT/Operating Income.

From that pre-tax return on capital employed (including the bottom during bear markets), we evaluate whether it is safe to leverage and to what degree. Leverage is an important component of the valuation because it can increase the return on equity, as long as the cost of debt is lower than the average return on capital employed. I define the max leverage as the level of debt that would make interest expense become up to 50% of EBIT during the downcycle, based on an average rate of 7.5%. Of course, this is subjective, and others may be happy with higher/lower leverage. In general, the trucking carriers shun leverage, and my model generally finds ‘excess leverage capacity’. For the ‘levered’ scenario for growth, equity returns, and valuation, I substract the excess leverage capacity from the market cap (this is like assuming the companies take debt to pay dividends or repurchase stock).

After accounting for debt, we can find the net earnings to equity across the cycle and compare it with the current market cap of the company to find the earnings yield of the name. If the company did not plan to grow, it could pay this earnings yield to the equity in the form of dividends or repurchases.

Finally, we can account for growth. Growth, assuming a constant P/E across the cycle-average earnings, is equivalent to return (if earnings grow 5% and the P/E is fixed, then the stock price will climb 5%). Of course, growth has to be financed, and the part that is financed with equity subtracts from the earnings yield above. If the company has a low return on capital employed, it will not be able to leverage much, and therefore it will need to finance most growth with earnings, thereby negating all or most of the earnings yield, and putting a cap on how fast it can grow safely. The growth expectation of the model is the lower of the revenue CAGR in the 2015-2025 period, and the funding capacity to leverage.

The combination of the expected earnings + growth yield, plus some qualitative factors, gives us an idea of whether the name is undervalued or overvalued today. I provide a model for each of the companies, showing how each segment trickles into the valuation and return expectation.

Comparability of the period

The period I am using to estimate the cycle-average pre-tax return on tangible capital employed goes from 2015 to 2025. It is a complex period that includes a huge bull (21/22) and a huge depression (23/25), which is preceded by almost a decade of very mild cycles in the 2015-2020 period of high American growth after the GFC. Some might believe such an average underestimates the true average return, because it includes a depression that is too deep and too long. In my opinion, this is at least offset by the precedent high-profitability period of 2015-2020, and the bull of 21/22. In fact, I believe the average probably overestimates future profitability, if anything. However, the use of the current downturn as the threshold for leverage might reduce the leverage capacity of these companies too much, compared to a normal cycle.

Why EBIT and not EBITDA? Why keep ROU?

Some companies present their ROIC or other capital return figures based on EBITDA, and after removing lease assets (ROU) from the denominator. I believe this is misleading, at least for this analysis.

Starting with EBITDA, D&A in trucking is a real expense very close to a cash expense. The truck will most definitely not run forever, and even if used for an extended period, it will start to generate problems in other portions of the cost equation (higher maintenance, lower average speed impacting labor costs, higher fuel consumption). If we calculate the returns on capital before D&A, we are ignoring that at the end of its life, the asset will have no salvage value. It is like an Uber driver who thinks he’s making a lot of money without considering that eventually he will need to purchase another car.

Regarding leases (which admittedly are a larger issue for logistics and LTL companies than for truckload carriers), the problem is the capacity to finance capital. All assets in the balance sheet need to pay a return (except those financed by working capital liabilities, which are removed from the denominator). Therefore, all assets need to earn a return. This is especially true for lease assets, which need to earn their D&A (otherwise the lessor is implicitly gifting the asset), and also a financial return. If we remove leases, we are overestimating the aggregate asset return of the company, and therefore its capacity to leverage (leases are a form of leverage).

Speculation motives

This method leaves out the goal of speculating on the cycle itself, i.e., going long above an estimate of long-term value because we believe the market will further overpay. Still, an estimate of what the companies might earn over the long-term, compared to the prices of stocks, is a gauge of whether the cycle (as reflected in the prices of stocks) is depressed, already buoyant, or even euphoric.

I also do not use long-term P/Es or P/Es from specific points in the cycle. That would imply outsourcing the return requirement to the market. If the market has in the past valued a name at 18x P/E over cycle-adjusted earnings, but I believe it is worth at most a 10x, and it currently trades at 13x, then in my opinion, it is overvalued, not undervalued. Again, speculating on the stock reaching 18x or even higher during the bull is valid, but it is not what we are focusing on here. That speculation is much more dependent on sentiment and market psychology than on fundamentals.

General conclusions

The ‘promise’ of the public carriers is that by owning large fleets in the thousands or dozens of thousands of trucks, they are able to gain all sorts of efficiencies in asset utilization, overhead dilution, and level of service to the customer that the majority of the small carriers, which make up the bulk of the for-hire market, cannot reach. It is a ‘bottom of the cost curve’ strategy based on scale, borrowing from the language used in other commodities to refer to producers that earn a premium margin on the market because they are always the lowest cost producers in bull or bear markets.

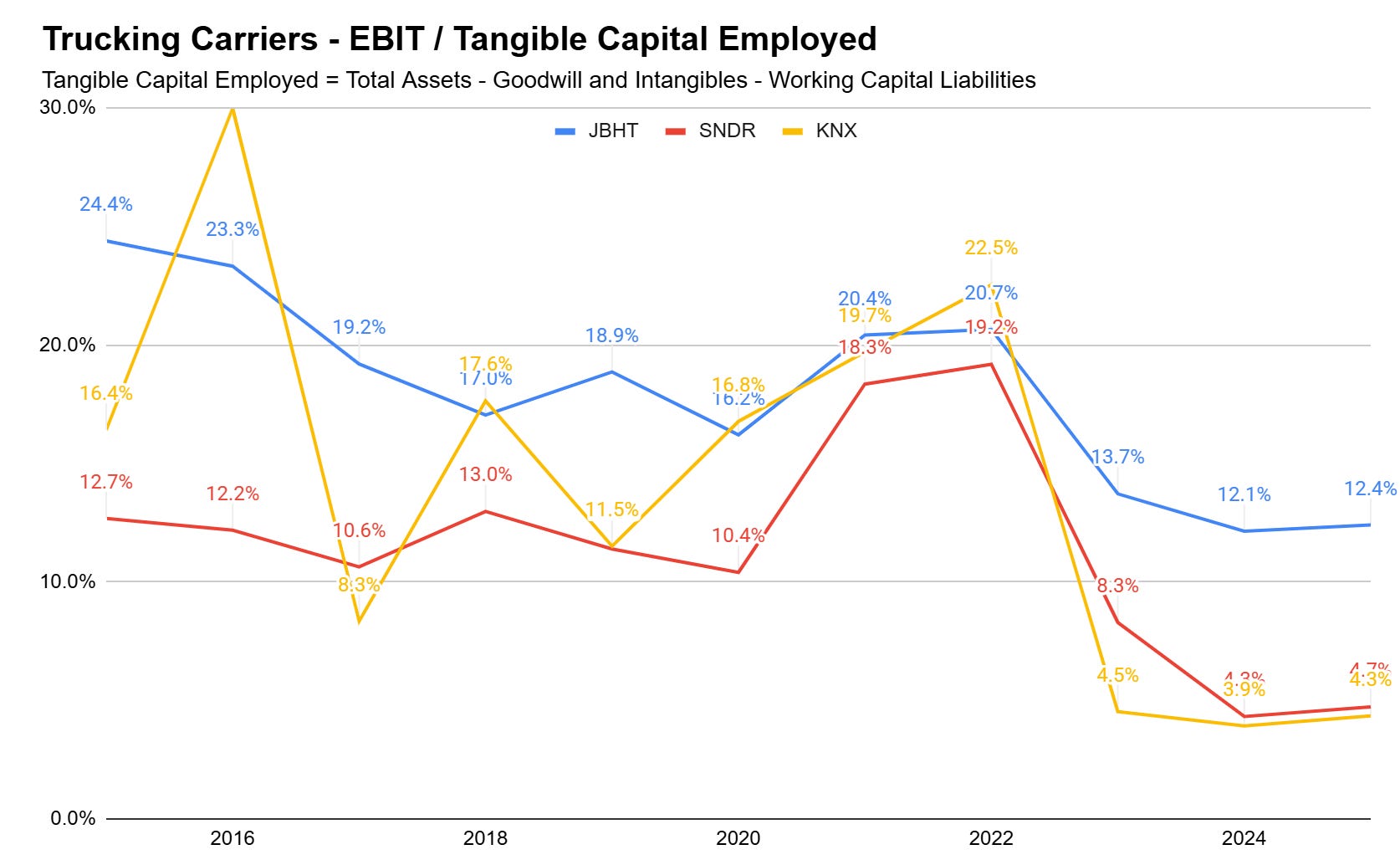

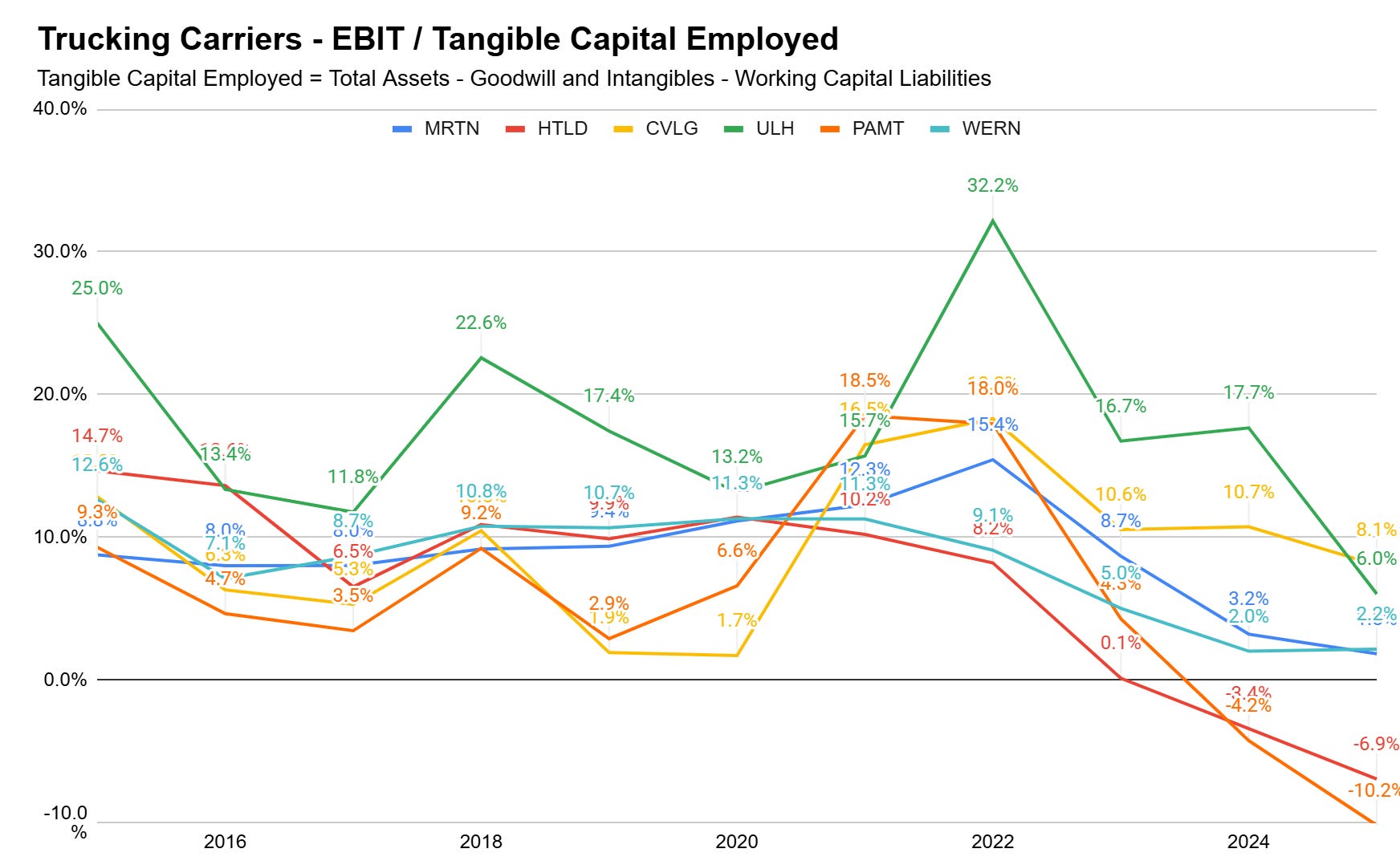

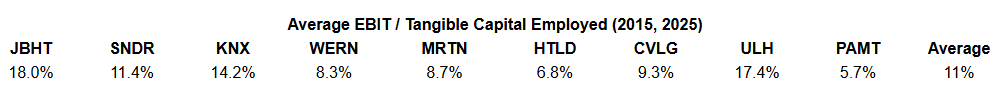

From what I have seen, however, that does not seem particularly true, except for the larger companies in the market (first chart below). The majority of the smaller companies covered (second chart below) cannot exceed a 10% pre-tax return on tangible capital employed except during bull markets. Some are not even making money operationally anymore.

A low pre-tax return on capital complicates leveraging (it becomes risky during downturns, except at small levels) and therefore does not allow for high (post-tax) returns on equity.

In general, this would not be a problem to take positions in the industry if the assets were sufficiently discounted, especially considering we still are in the doldrums of a long downcycle. Unfortunately, I find that in most cases, the stocks are not discounted at all, but rather expensive already.

Assuming the companies are able to earn the average return from the past decade, the majority offer a return expectation (growth + distributable earnings yield) of less than 10%.

To me, the ‘opportunity’ presented by the stocks on a long-term fundamental basis looks like this: “If everything goes well, we go back to the post-GFC earnings environment, and we allocate capital efficiently, leveraging just enough to maximize equity returns while keeping risk at bay, and return all excess funds to you, your return is still less than 10%”. That does not sound attractive to me, especially for some companies that would rank quite low in the quality scale.

That does not mean this will remain like this forever. Many of these stocks have appreciated rapidly in the past three months, on the expectation of a cycle turn. If the turn did not become a reality, then the stocks might decrease to more attractive positions.

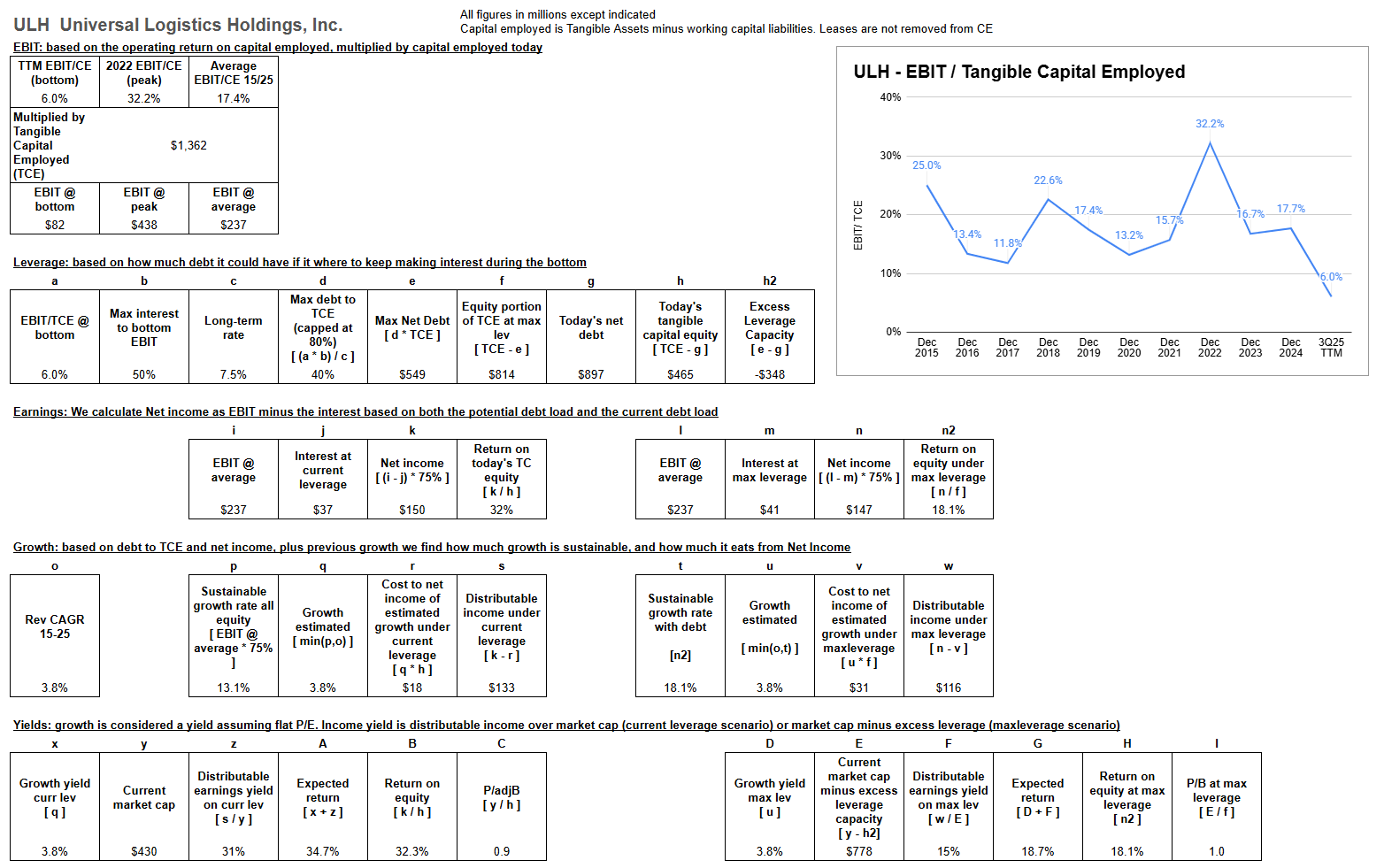

One speculative play

I have found that one stock (ULH) does offer a very interesting potential return (30% distributable earnings yield) if it is able to return to pre-downturn returns on capital. Interestingly, its returns have only recently collapsed, driven less by the overall cycle than by an acquisition and its specific specialty-industry cycle.

Of course, this ‘opportunity’ does not come without risk. The company is fairly levered, and at least in its last quarterly report, it was not able to cover interest from EBIT.

In my opinion, it is a speculative levered (operationally and financially) play into its specific trucking cycle recovery. You can find the analysis at the end of the article, behind the paywall.

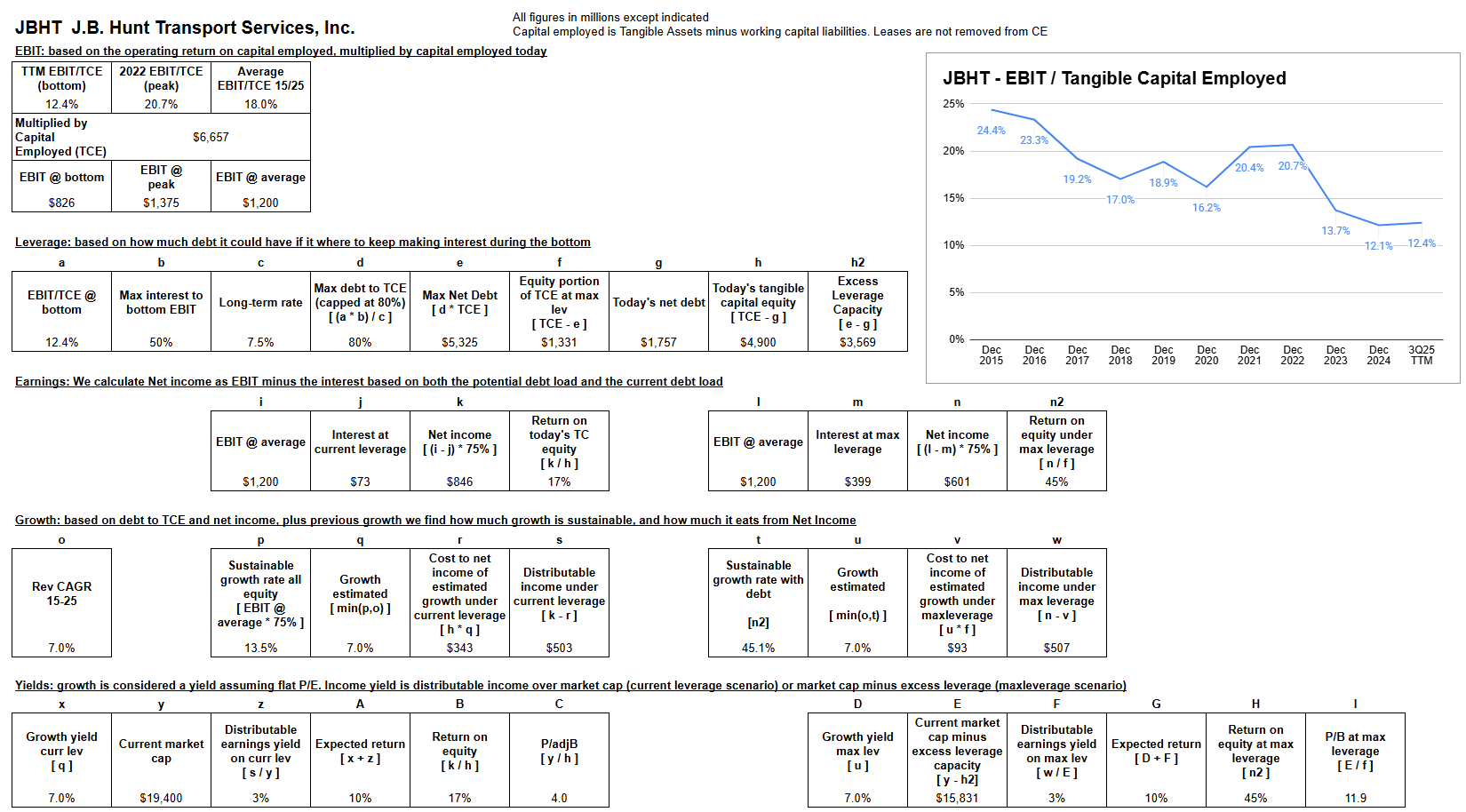

J.B. Hunt Transport Services - JBHT

J.B. Hunt is probably the most qualitative play among truckload carriers, as shown in a fairly elevated average and even bottom return on tangible capital employed. Its lowest returns are better than the best returns of most other companies.

J.B. Hunt’s breadwinner segments are intermodal and dedicated (82% of assets, 85/95% of operating income). The company also participates in areas of logistics like last-mile delivery and asset-light brokerage, and has a small for-hire truckload operation, but these segments are less relevant.

In intermodal, the company is the market leader. I estimate the company has about 10/15% of the market ($6/7 billion in revenues versus ~$50 billion for the intermodal market). This might provide it with scale and long-term contracts that provide certain stability. Intermodal is a segment that tends to remain in demand in bear markets because companies try to cut costs at the expense of speed. During bulls, railroads tend to generate delays, and companies prefer to pay for full trucking freight. Still, pricing power and margins have declined significantly.

In dedicated the company also claims to be the largest, but on a much more fragmented market (I believe less than 5% of a $100 billion market). Still, the company has scale with ~13 thousand trucks servicing dedicated customers alone. The stability of this segment can be seen in a relatively flat EBIT/Assets of 18/17/17% in 2022/23/24, compared 25/17/12% for intermodal during the same period.

Overall, the position has a moat, which might be eroding slowly (as shown in a decreasing EBIT/TCE trend), but that is still higher during the bottom than most other carriers earn during their peaks.

The company’s founding family still has 18% in the company, and most members of management have been with the company for 2+ decades. Another quality point for JBHT is that it is the only company I have evaluated on trucking that discloses assets per segment, a key measure to understand segment-level returns on capital, and therefore judge capital allocation decisions.

Unfortunately, this ‘quality’ has a huge price. Both using a levered and unlevered model (the company could sustain a lot more debt than it does today, even assuming margins do not improve), very good average returns on equity (of 17% as currently levered and up to 45% if levered significantly but still conservatively considering past returns on capital), are offset by multiples of book value that cancel that potential return (4x and 11x respectively). The distributable earnings yield under my assumptions is LSD, and after adding some growth (CAGR of 7% since 2015), the situation barely makes a moderate return. I think JBHT has already priced the recovery, without considering the risks of a permanently lower average profitability level forward.

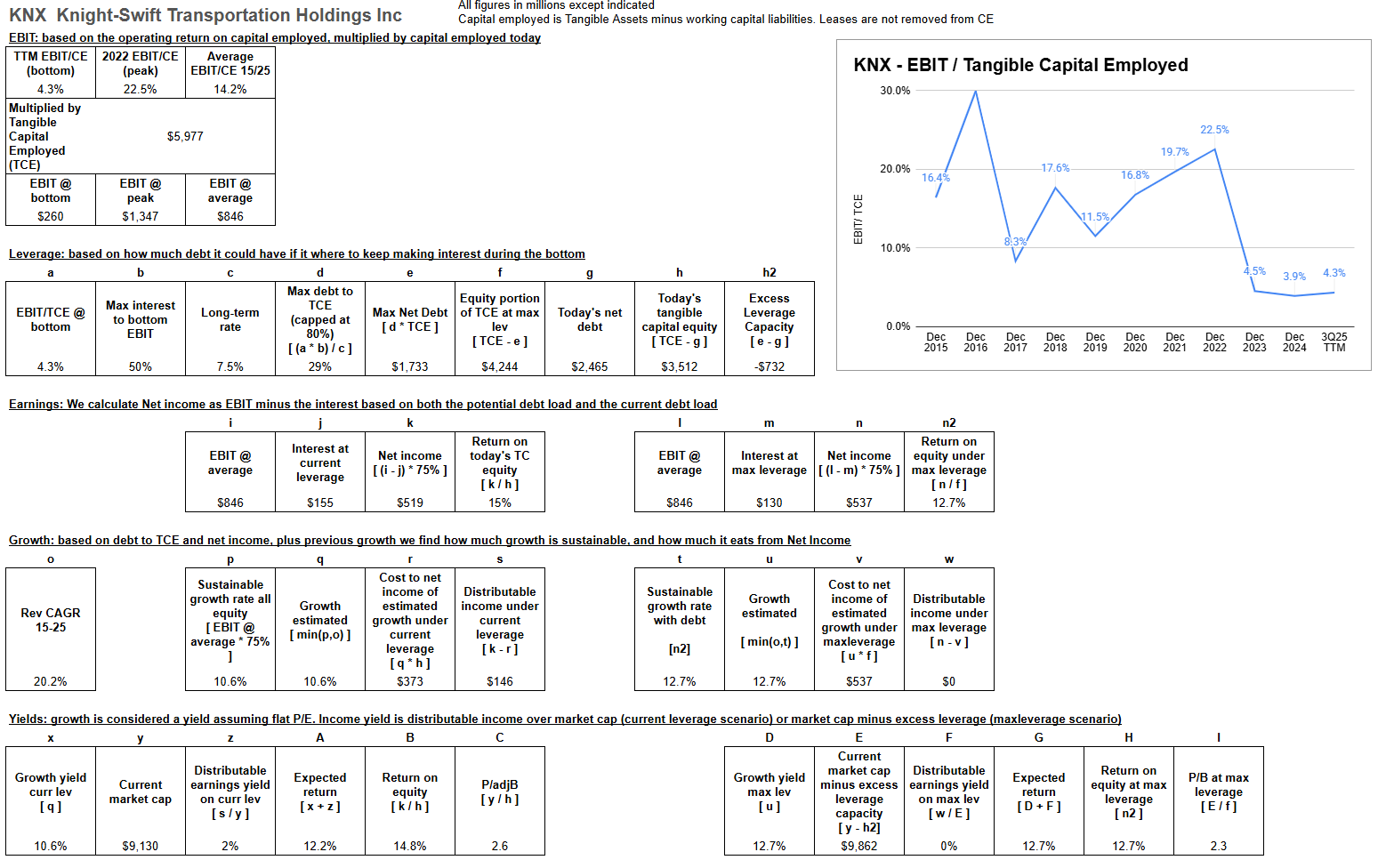

Knight-Swift Transportation - KNX

Knight-Swift is (or was) another quality name in truckload.

Interestingly, KNX managed to do that while being one of the few companies with (and maintaining) significant exposure to the for-hire truckload segment, which they call over-the-road (referring to longer distances than regional) truckload (45% of revenues in 2024, above 50% before the pandemic). This might be a good example of scale, with 22 thousand trucks in the truckload segment alone (about the same number as JBHT for all its operations). Originally, I believed a larger route distance might be a source of moat (regional players less able to compete in transcontinental), but this is not the case, with an average trip of ~400mi (LA to SF), which is about the same as most other carriers.

Besides for-hire truckload, the company also has dedicated (18% of revenues), logistics (9%), intermodal (6%), and less-than-truckload (18%) businesses.

The recent fall to very low levels of asset profitability is explained by the company’s mix (for-hire truckload is the most impacted segment during downturns and also the one that recovers the first and reaps the most benefits during upturns), but also by the acquisition, at the worst cyclical point possible (2021/22), of its LTL business.

The management of an LTL network is very different from TL (much higher fixed costs and network complexity), probably pressuring returns on capital. The company’s LTL segment has significantly lower margins than peers (12% at peak and 5% today versus 12% for SAIA and 25% for ODFL on a TTM basis).

This low level of current returns impacts the level of leverage allowed by my model, which, for safety reasons, would recommend the company to delever rather than lever up. If current low returns are a one-time thing and not representative of future cycle-bottom returns, then the company might leverage more and enhance returns on equity. Of course, this also embeds the optimistic assumption that returns will not be permanently lower.

Still, using average returns, the distributable earnings yield is LSD, which, added to the financeable growth (of 10%, hard to do without acquisitions, which have proved challenging in the past), reaches a higher low-teens level. In my opinion, this is not attractive given the embedded optimism of a return to the mean.

Still, KNX is probably one of the most levered plays to the cycle, because of its debt, and because it participates in the most rate-sensitive market.

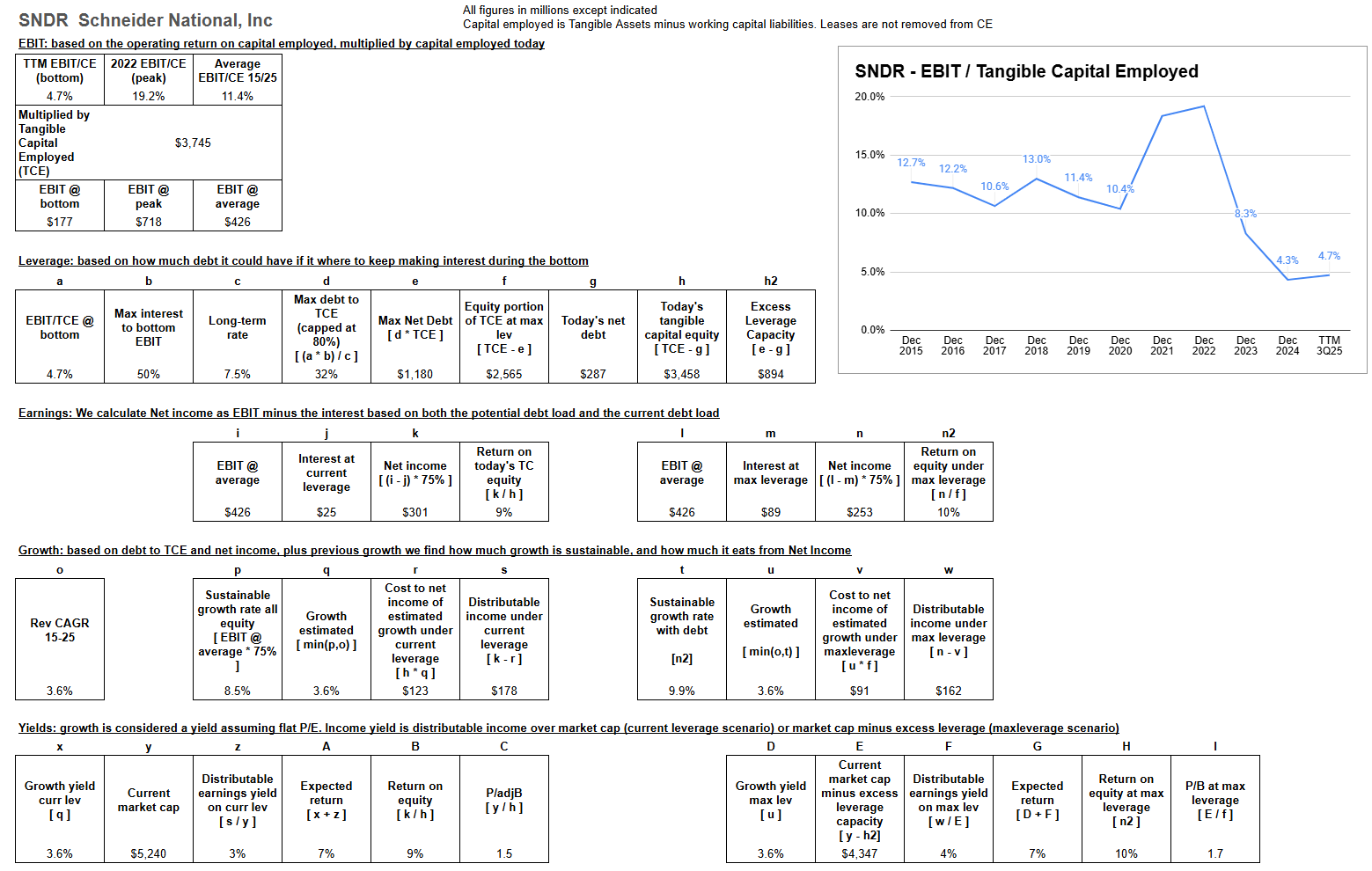

Schneider National - SNDR

With Schneider National, we already have a significant fall in quality, as evidenced by lower average EBIT/TCE, and much lower during the bottom, removing potential leveraging capacity.

Schneider is an example of a company that has shunned for-hire truckload (Network in the charts below) in favor of dedicated. The company is already 50% smaller than J.B. Hunt in terms of revenues (its dedicated segment is 1/4 of JBHT’s, and intermodal is 1/6). The company also has a larger logistics segment (~20% of operating income), which should push returns on tangible capital upwards (low tangible capital requirements).

Schneider’s quality seems lower not only on the return on capital of the aggregate operation, but also on the volatility of the segments. Whereas in JBHT we saw the dedicated segment maintaining fairly stable margins, in SNDR the truckload segment (which admittedly includes a still relevant 1/3 of for-hire) fell from ~16% in 2022 to less than 4% today.

Again, even assuming pre-COVID returns, the expected returns for the company are MSD to HSD at best, and the premium to book is too high given the optimism. The stock price seems like a clear indicator of cyclical exhaustion.

Schneider is controlled by the founding family with a ~70% economic stake and 95% vote share.

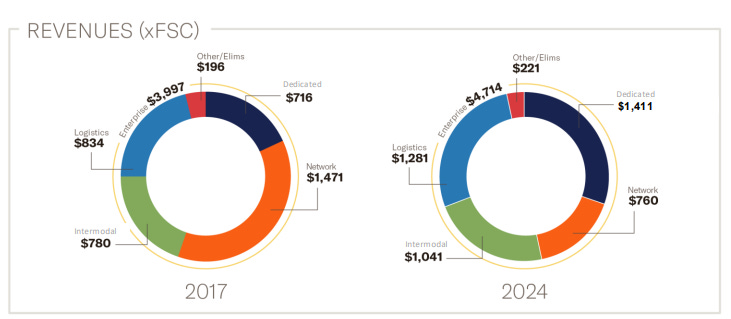

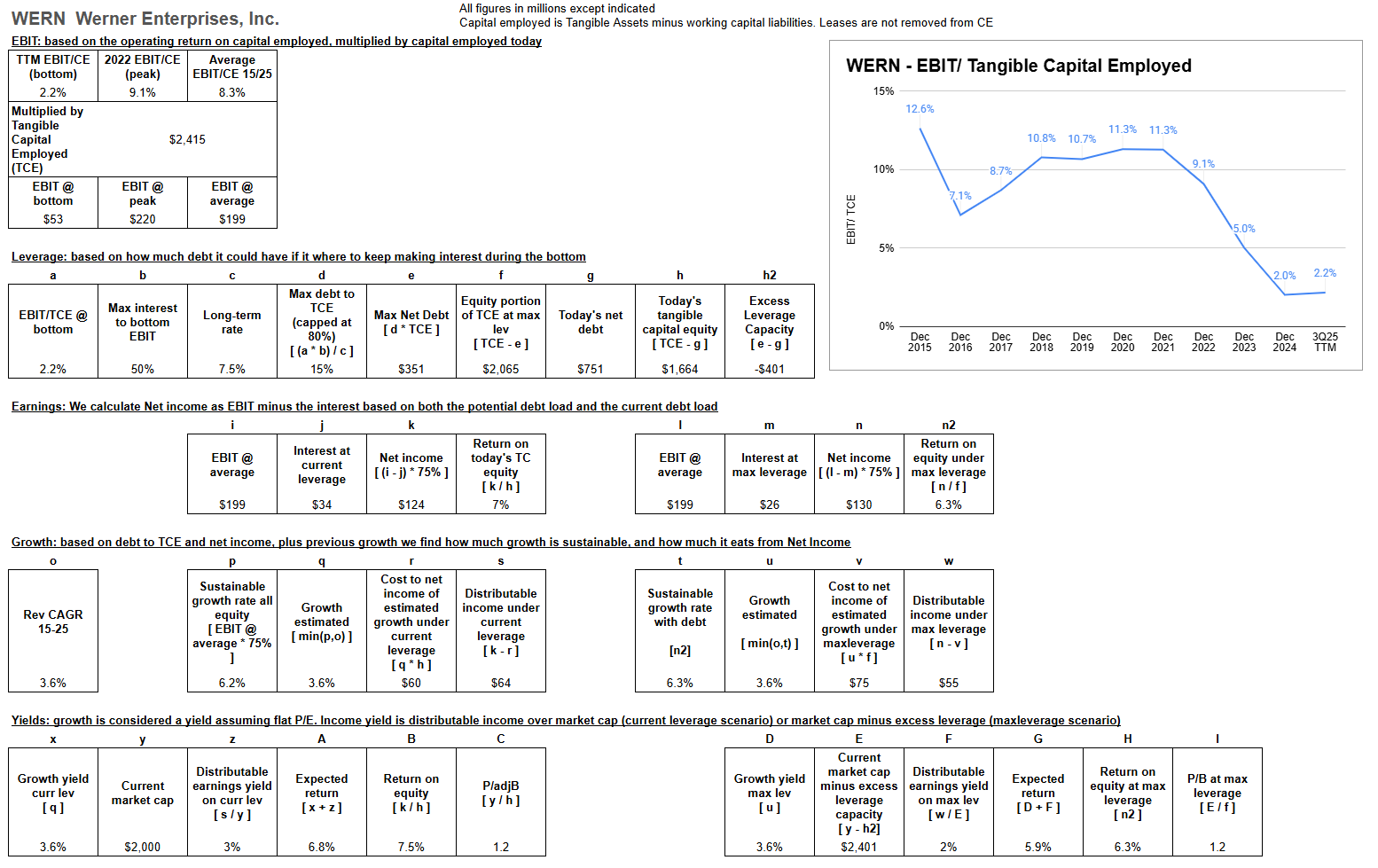

Wern Enterprises - WERN

Werner Enterprises is another step down in the quality ladder (peak returns do not reach JBHT’s bottom returns).

The company shows that intrinsic factors are more relevant than the company's segments. It derives 50% of revenues from dedicated (theoretically more protected) and 25% from logistics (theoretically better return on tangible capital), with the remaining 25% from one-way truckload. However, its returns are not very impressive.

The cycle is obviously way below the previous average (even going back to the year 2000, EBIT/Total Assets ranged between 8% and 12%), but the company also made four acquisitions at peak cycle in 21/22, tripling its net debt.

It baffles me how a name like this can trade at 20x cycle-average earnings (which assume a return on tangible capital of 8% vs 2% today).

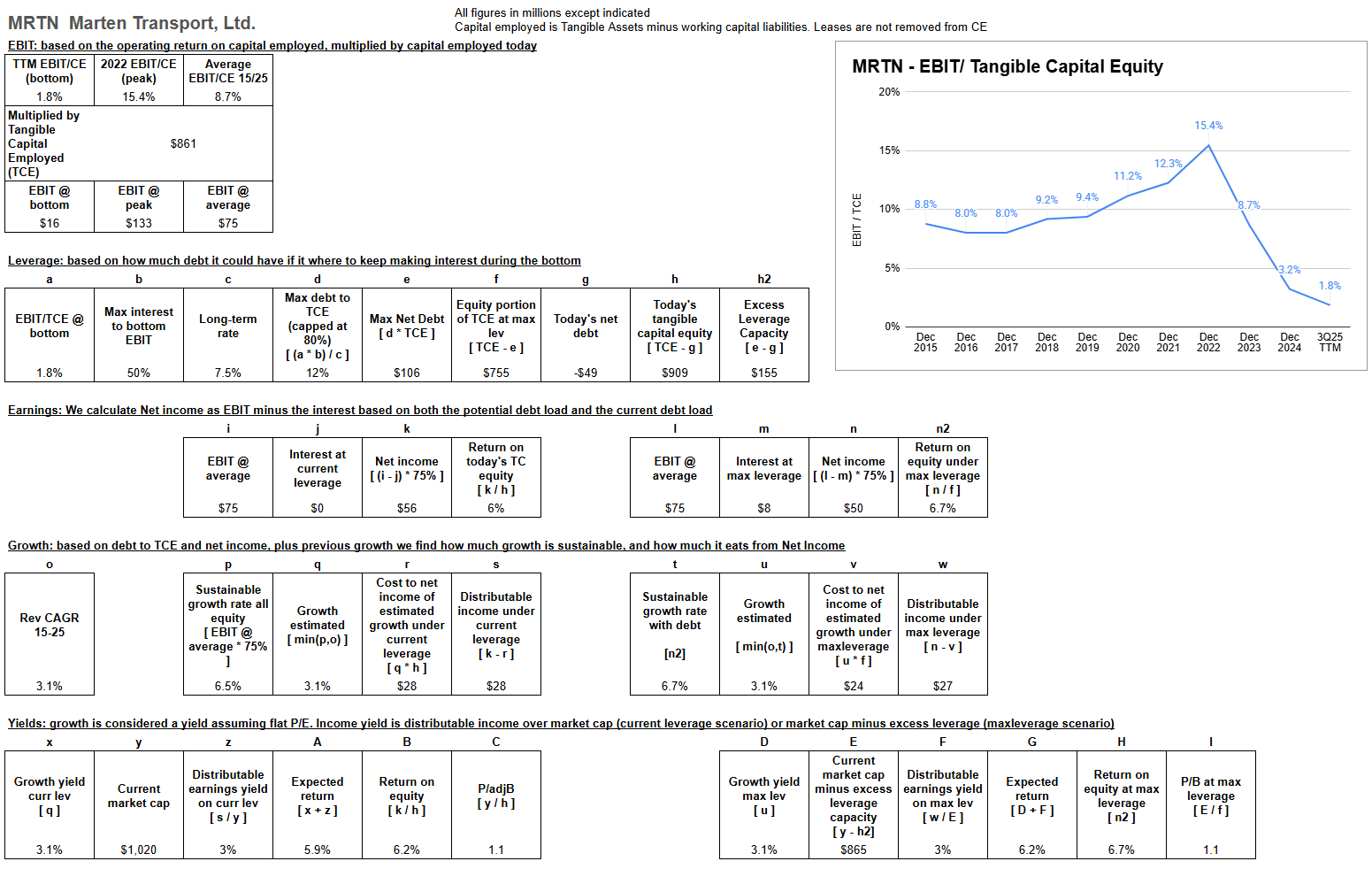

Marten Transport - MRTN

Marten Transport’s business is refrigerated loads. The company participates in for-hire (~50% of revenues), dedicated (~30%), and brokerage (~20%), but in all cases, refrigerated makes up 2/3 or more of the loads. The company owned an intermodal segment, but it was sold to Hub Group (HUBG). According to Jandel Research, the company is the 7th largest in the refrigerated freight industry nationally.

The average trip distance for MRTN is regional (~400 miles or the distance between LA and SF), potentially impacting the benefits of scale of a national player.

Obviously, the company is under a lot of pressure today, with truckload being unprofitable on an operational basis and dragging the rest of the business. Still, not even in this case do we get relatively attractive prices, with return expectations barely reaching MSD, with or without growth, and with or without leverage.

The company was managed and partially owned by the founding family. The son of the founder was CEO until 2021 and has recently returned to the position, and owns 22% of the shares. Another Marten surname shareholder owns 6.5%.

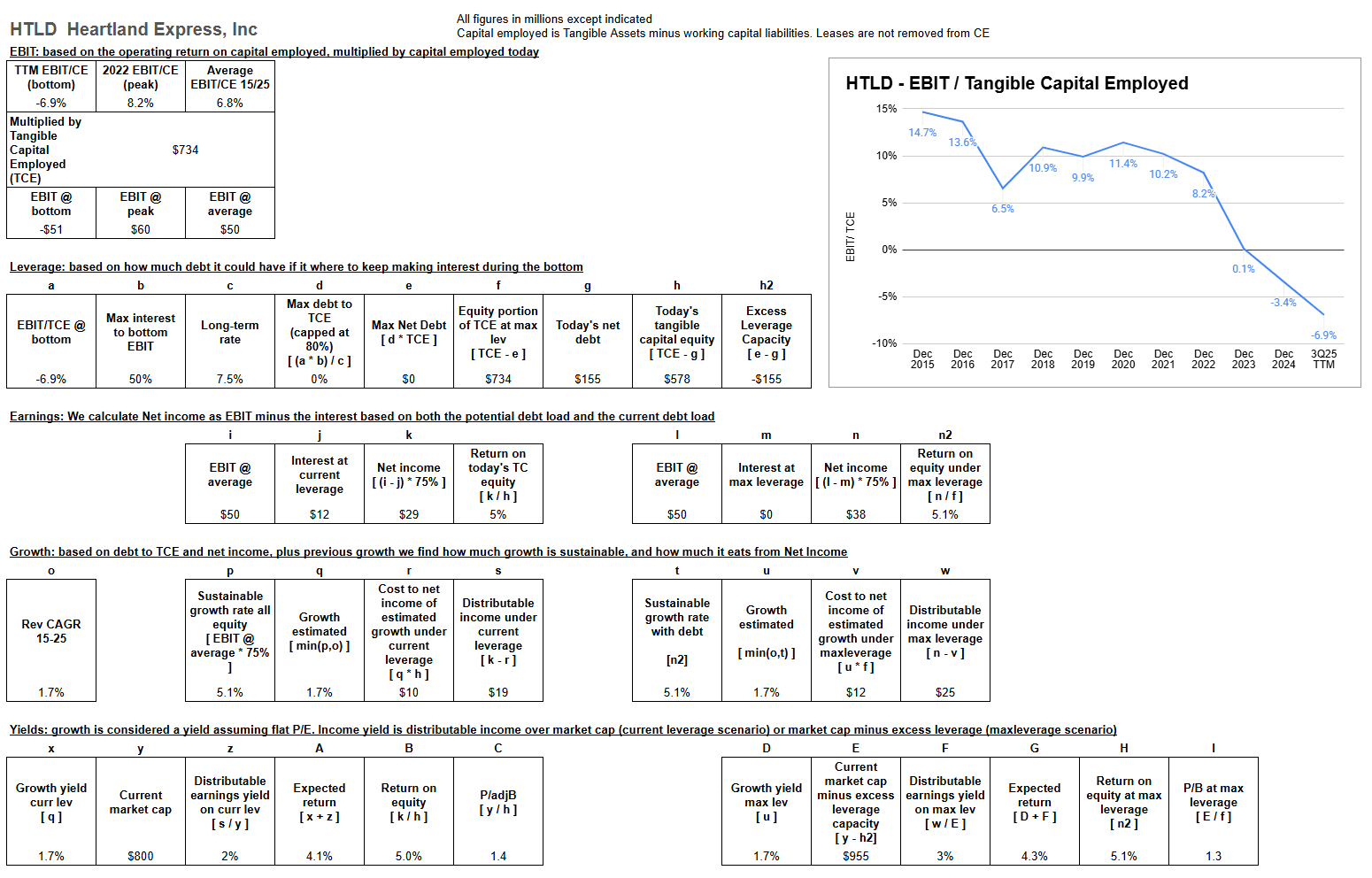

Heartland Express - HTLD

We are now entering the territory of challenged, very marginal names.

The company does mostly for-hire truckload, on a fairly regional basis (~500 mi average trip). The returns were not too bad before the pandemic, but then the company made several acquisitions in the peak cycle, reducing returns and increasing leverage (which is being repaid from underinvestment). It has been operationally unprofitable for two years.

The company is losing drivers (potentially related to underinvestment and selling trucks), which removes some of the upside during an upturn.

The average EBIT/TCE is influenced by fairly negative returns for two years already, but still, even if we assume the average ROTCE is 10%, we get an earnings yield without growth of ~6%, and an expected return with growth of about 7%. I truly cannot understand how a name so challenged trades at 17x+ optimistic earnings assumptions.

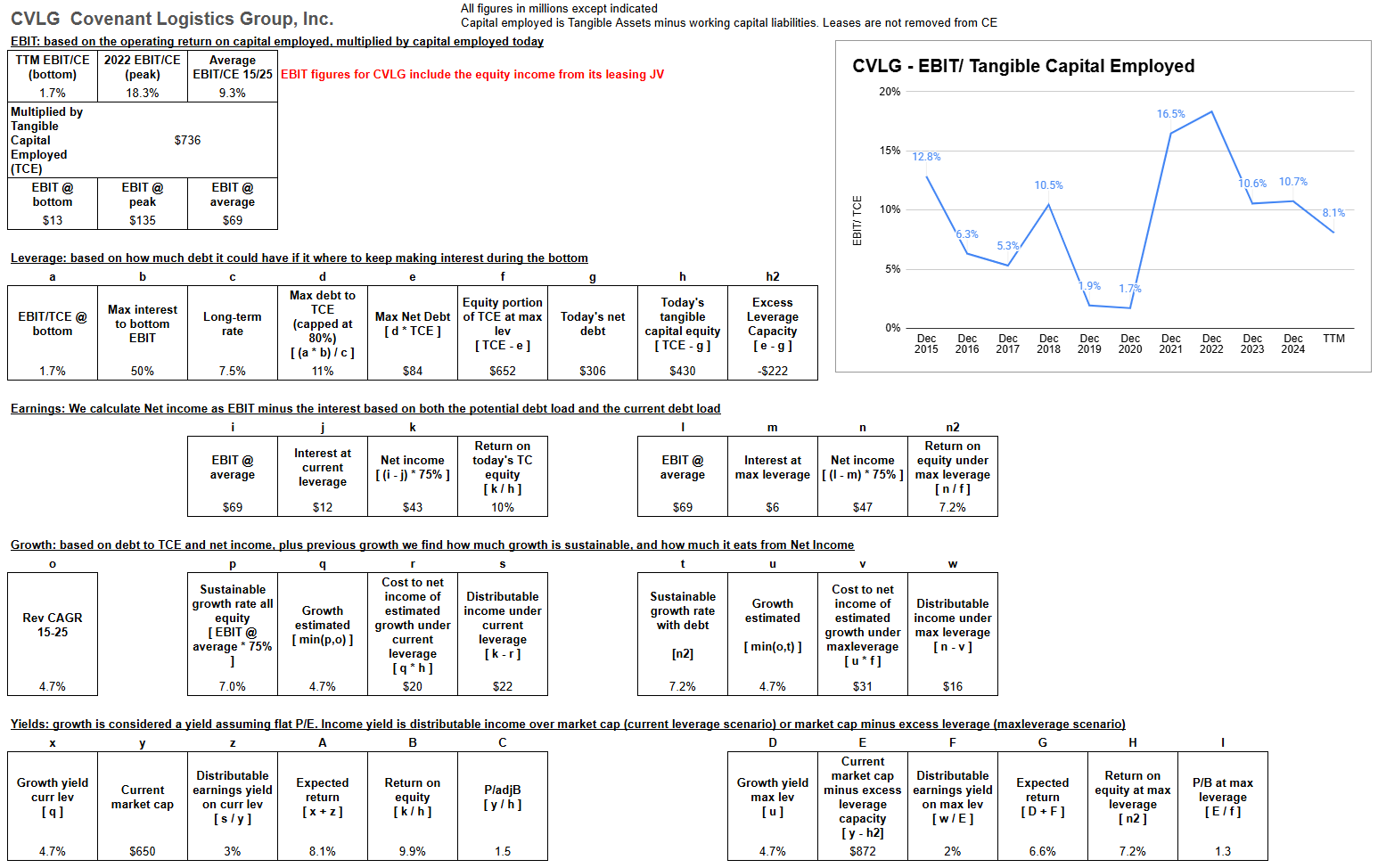

Covenant Logistics - CVLG

Covenant is more of a mix of segments.

The company derives 1/3 of revenues from Expedited (a modality in which two drivers share a truck to rest and drive continually), 1/3 comes from dedicated, and 1/3 comes from logistics (including a relatively higher-service subsegment called managed freight at 70% of logistics revenues).

In addition, the company owns part of a truck leasing JV that adds 1/3 of operating income, below the operating income line, as it is accounted via the equity method (in this case, I have the JV’s share of income to CVLG’s EBIT for the calculations above).

It is the only name performing better today than before the pandemic. This might be related to acquisitions (2018 and 2023 in Dedicated, 2022 in Expedited), and to the growth of the JV (from 1/10th of operating income to 1/3 today), which increases the EBIT/TCE because the only asset considered is the equity portion of the JV (it is a return on equity masking as EBIT/TCE).

CVLG’s CEO and his wife own 25% of the company, and have ~40% of the votes.

The returns expectations are not very good on an average basis, but this is admittedly less valid as an average for CVLG, given its business has improved instead of weakening. Still, even assuming an average return of 12% instead of 9.3% today, the return to shareholders climbs to low-teens only.

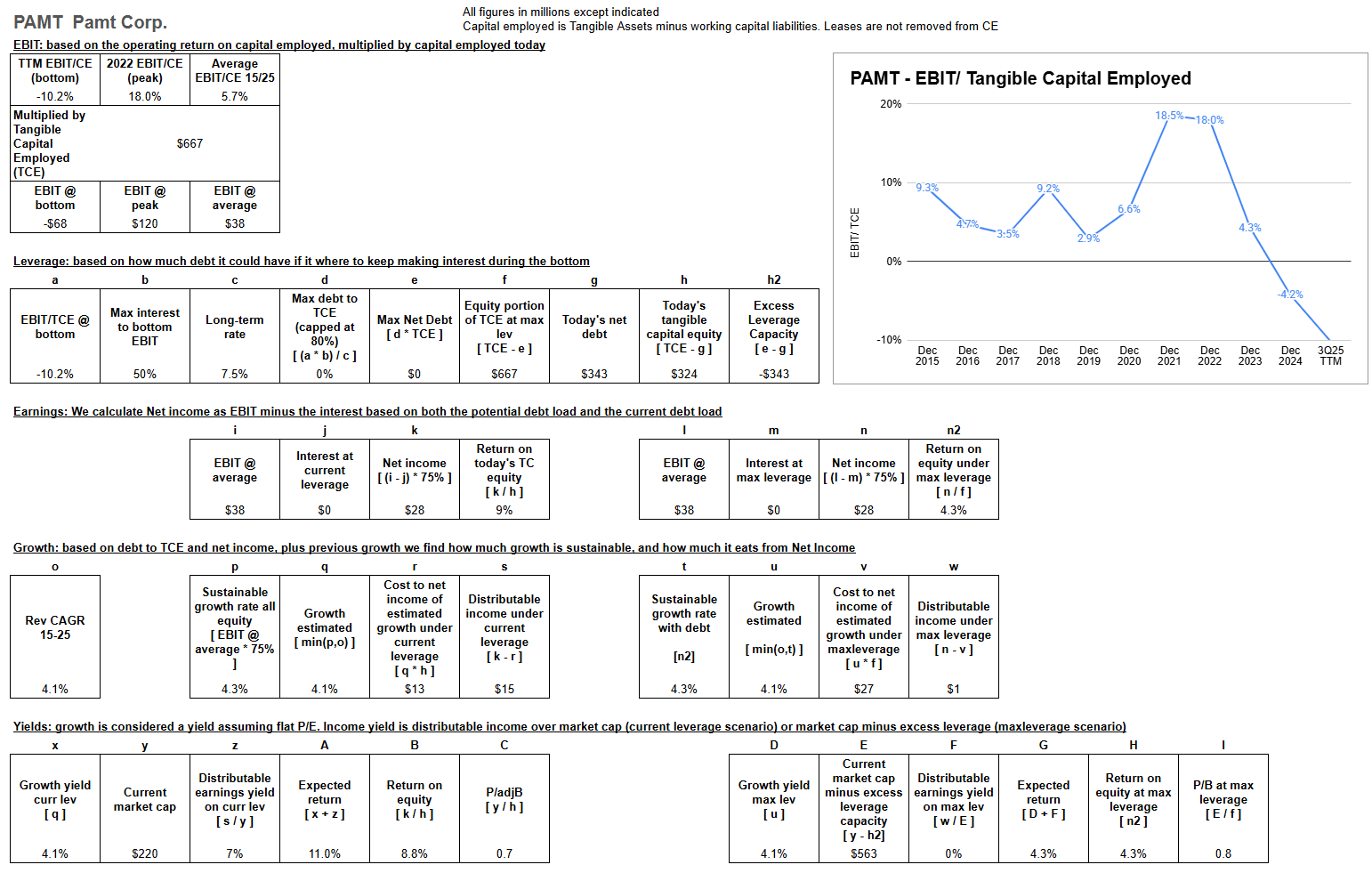

PAMT Corp - PAMT

PAMT Corporation is another operationally unprofitable carrier, and it’s the company with the lowest market cap covered in this article. The average EBIT/TCE returns of the company are among the lowest in the space, even before the pandemic.

The company’s business is almost entirely for-hire truckload (70% of revenues), with additional brokerage operations (30%), which are, nonetheless, lumped into the same segment. The company has a significant exposure to Mexican transportation (~50% of revenues), adding to the challenges of the cycle within the US.

Similar to HTLD, another for-hire focused carrier, the company’s margins collapsed because of its high exposure to the most commoditized sector. Revenues also decreased by more than 30% from the peak in 2022, in part driven by rates but also by disinvestment.

To this, we need to add leverage (the company would need at least 2/3% operating margins to cover interest, versus 8% negative margins today).

To cover interest and maintain cash, PAMT is actually net divesting in 9M25, reducing the potential for capturing a turnover in the cycle.

Considering its really challenged position, its low quality before current challenges, and the fact that its scale reduction will challenge full capture of the up-cycle, the company offers only a moderate HSD/LDD return expectation, assuming things improve a lot.

PAMT is the ‘sibling’ of Universal Logistics Holdings (ULH), owned by the same controlling family.

Universal Logistics Holdings - ULH

Disclaimer: I own shares of Universal Logistics Holdings (ULH).